At NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida, workers tow the space shuttle orbiter Columbia from the Orbiter Processing Facility to the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB).

Credit: NASA

Crew of STS-2 works through the night on shortened mission.

On November 12, 1981, 40 years ago this month, Commander Joe H. Engle and Pilot Richard H. Truly launched from Kennedy Space Center on the Space Shuttle Columbia. STS-2 was Columbia’s second spaceflight, making it the first reusable spacecraft to ever return to space.

Engle was an accomplished test pilot who had already earned astronaut wings before joining NASA, having flown the X-15 to a maximum speed of Mach 5.71 and a maximum altitude of 280,600 ft., well above the 50-mile demarcation line to space recognized at the time. Truly was also a skilled pilot, having flown F-8 Crusaders aboard the aircraft carriers USS Intrepid and USS Enterprise.

Although the mission objectives appeared less demanding than those of STS-1, Engle noted that there was a growing realization that simply positioning and check-listing the shuttle’s more than 1,500 switches and circuit breakers at precise times presented a challenge for a two-member crew that was also working to complete other tasks.

STS-2 astronauts Joe H. Engle, left, and Richard H. Truly arrive at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

Credit: NASA

The flight got off to a rocky start when one of Columbia’s three fuel cells failed just two hours into the mission. The cells were a vital component of the shuttle’s electrical power system, employing a chemical reaction to generate all of the power required to fly and land the shuttle. The failure also resulted in the crew’s potable water being infused with hydrogen gas bubbles, making it unpleasant to drink. Flight rules required that the spaceflight be shortened. The original 125 hours was reduced to 54 hours.

“We were disappointed,” Engle recalled in an oral history. But he and Truly understood and accepted the decision. “… there was no way of telling that it was not a generic failure, that the other two might follow, and, of course, without fuel cells, without electricity, the vehicle is not controllable.”

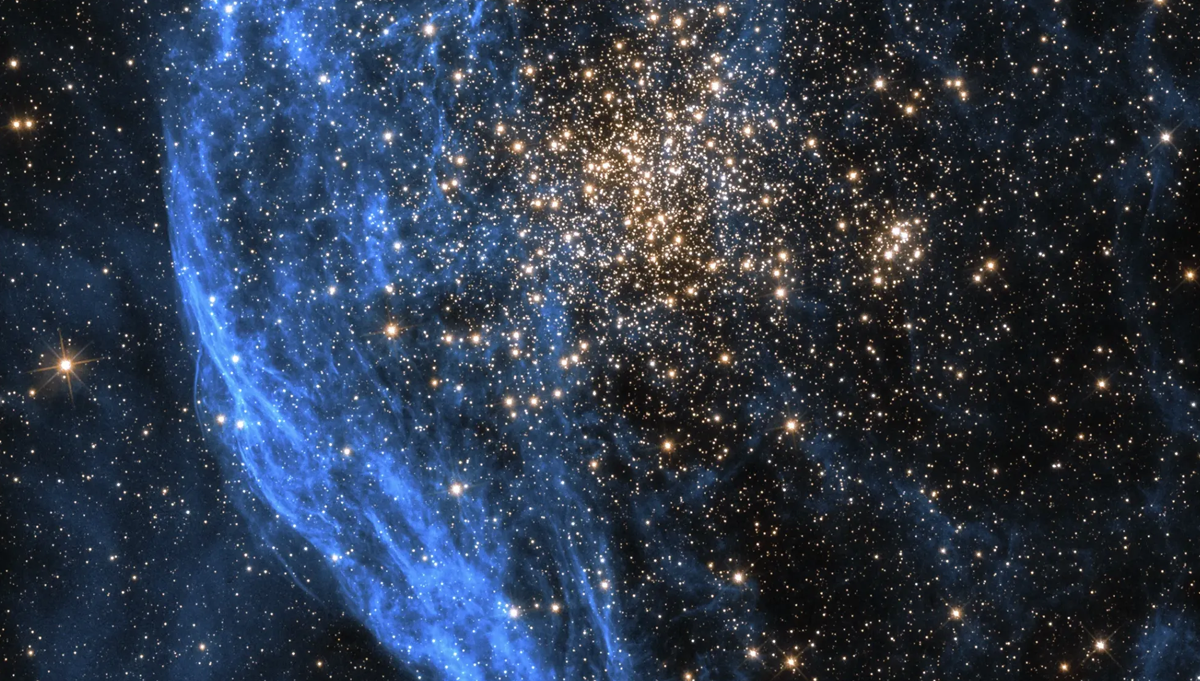

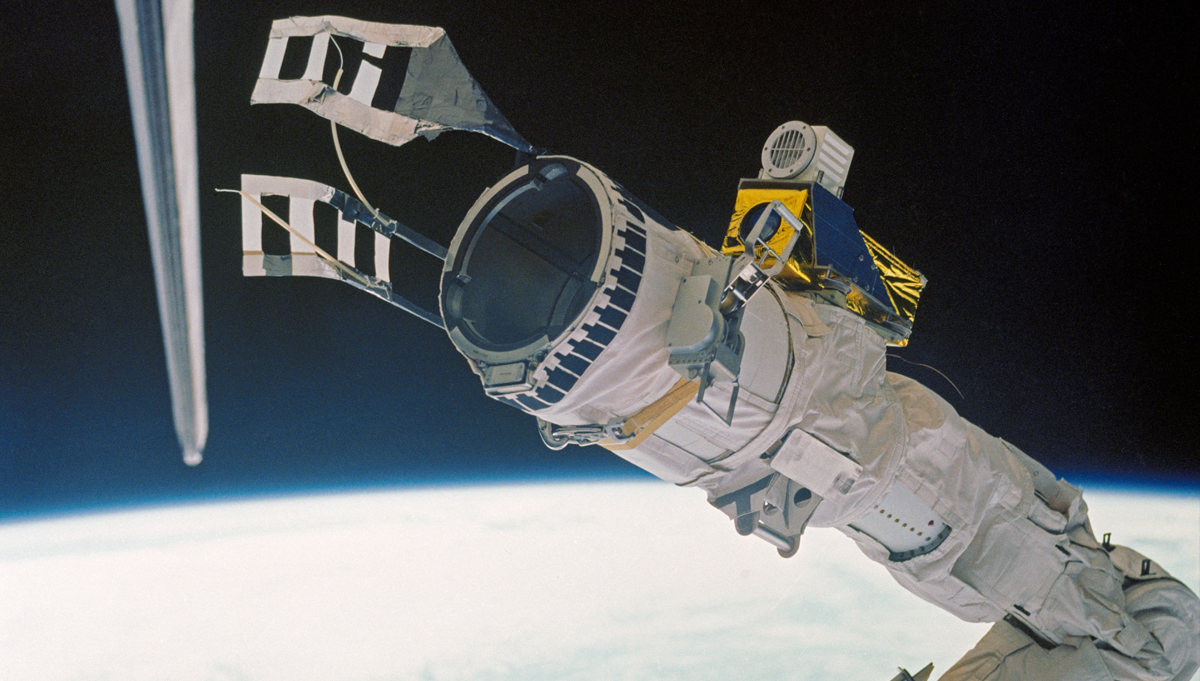

STS-2 mission objectives included fully testing the shuttle’s Remote Manipulator System (RMS), a 50 ft. long, 15 in. diameter robotic arm, with joints that mimicked the human arm. The RMS would play a crucial role in 90 shuttle missions, from deploying satellites to anchoring astronauts during extravehicular activities. STS-2 was its first full test in space. With their time in space limited, Engle and Truly decided to work through their last night in orbit.

“When our sleep cycle was approaching, we did, in fact, power down some of the systems and we did tell Mission Control goodnight, but as soon as we went LOS, loss of signal, from the ground station, then we got busy and scrambled and cranked up the remote manipulator arm and ran through the sequence of tests for the arm, ran through as much of the other data that we could, got as much done as we could during the night,” he said.

On STS-2, Engle and Truly tested the Canadarm (Remote Manipulator System) for the first time in space.

Credit: NASA

“Then the next morning, when the wakeup call came from the ground, why, we tried to pretend like we were sleepy and just waking up,” Engle added. The strategy enabled Engle and Truly to complete 90 percent of the mission’s objectives in less than half the time originally planned.

Reentry would present a fresh set of challenges for the astronauts. Engle, with his background flying the X-15, was assigned to perform 29 flight maneuvers from Mach 24 down to subsonic speeds. The maneuvers would be the fastest ever performed manually and would generate data about the shuttle’s performance near its limits, data that would be added to its computer programs to aid future reentries.

“The winds were coming up at Edwards. We hadn’t had any sleep the night before, and we were dehydrated as could be. … Dick had the cue card, and the plan was for him to read off the Mach number and the condition for the maneuver and what the maneuver was going to be, just to remind me of what these twenty-nine maneuvers were, so we did them precisely right on the way in. He had replaced his scopolamine patch and put on a fresh one. The atmosphere was dry in the Orbiter and we both were rubbing our eyes. We weren’t aware that the stuff that’s in a scopolamine patch dilates your eyes,” Engle recalled.

As Engle prepared for the first maneuver, he checked the conditions with Truly, who looked over the checklist and replied he couldn’t see.

“So, I thought, ‘This is going to be a pretty good, interesting entry. We got a fuel cell down. We got a broke bird. We got winds coming up at Edwards. We got no sleep. We’re thirsty and we’re dehydrated, and now my PLT’s [Pilot] gone blind,” Engle recalled with a laugh. Truly rallied though, and Engle had committed the maneuvers to memory before launch, so they worked through the list to provide the critical data.

This view of the space shuttle Columbia (STS-2) was made with a hand-held 70mm camera in the rear station of the T-38 chase plane. Mission specialist/astronaut Kathryn D. Sullivan exposed the frame as astronauts Joe N. Engle and Richard H. Truly aboard the Columbia guided the vehicle to an unpowered but smooth landing on the desert area of Edwards Air Force base in California.

Credit: NASA

STS-2 landed at Edwards Air Force Base in California on November 14, 1981. It was a homecoming for Truly and Engle, who served as crew 2 for the five Approach and Landing Tests conducted there with Enterprise. “I think one of the greatest feelings that I’ve had in the space program since I got here, was rolling out on final and seeing the dry lakebed out there, because I’d spent so much time out there, and I dearly love Edwards and the people out there,” Engle recalled.

Engle went on to serve as Commander of STS-51-I and as Deputy Associate Administrator for Manned Space Flight at NASA Headquarters from March to December 1982. Truly went on to Command STS-8 and become the first astronaut to serve as NASA Administrator, from May 1989 to May 1992.

Visit APPEL KS’s Shuttle Era Resources Page to learn more about STS-2 and the 134 other shuttle missions, missions that deployed key satellites, repaired the Hubble Space Telescope, enabled important new research, and were instrumental in construction of the International Space Station. The Shuttle Era Resources Page also contains important resources on the Challenger and Columbia tragedies and enduring lessons learned.