Earth can sometimes feel like the last place you’d want to be. Indeed, a number of explorers have devised inventive ways to move civilization off this planet.

It’s no surprise: The promise of a better life in the mysterious beyond can be seductive. But the fact is the more we learn about out there the more we realize how special it is here. The first astronauts to look from space back at Earth, a “pale blue dot, the only home we’ve ever known,” as scientist Carl Sagan once wrote, saw a beautiful, delicate world that is perfectly suited to the bounty of life it supports.

“When I looked up and saw the Earth coming up on this very stark, beat up lunar horizon, an Earth that was the only color that we could see, a very fragile looking Earth, a very delicate looking Earth, I was immediately almost overcome by the thought that here we came all this way to the Moon, and yet the most significant thing we’re seeing is our own home planet, the Earth,” said William Anders, a crew member on Apollo 8, the first crewed mission to the Moon.

On this 50th anniversary of Earth Day on April 22, we reflect on nine reasons Earth is the best place to live:

1. We can take deep, cleansing breaths

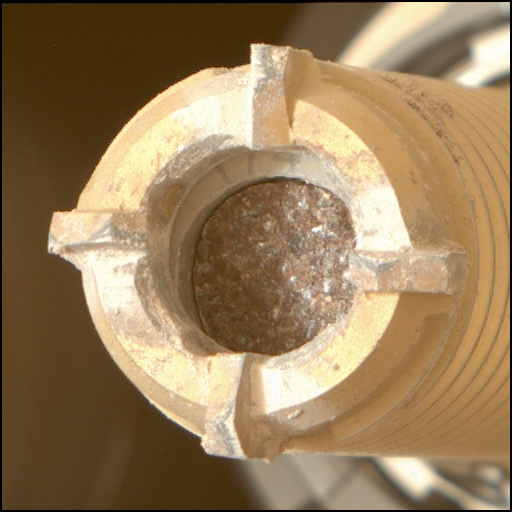

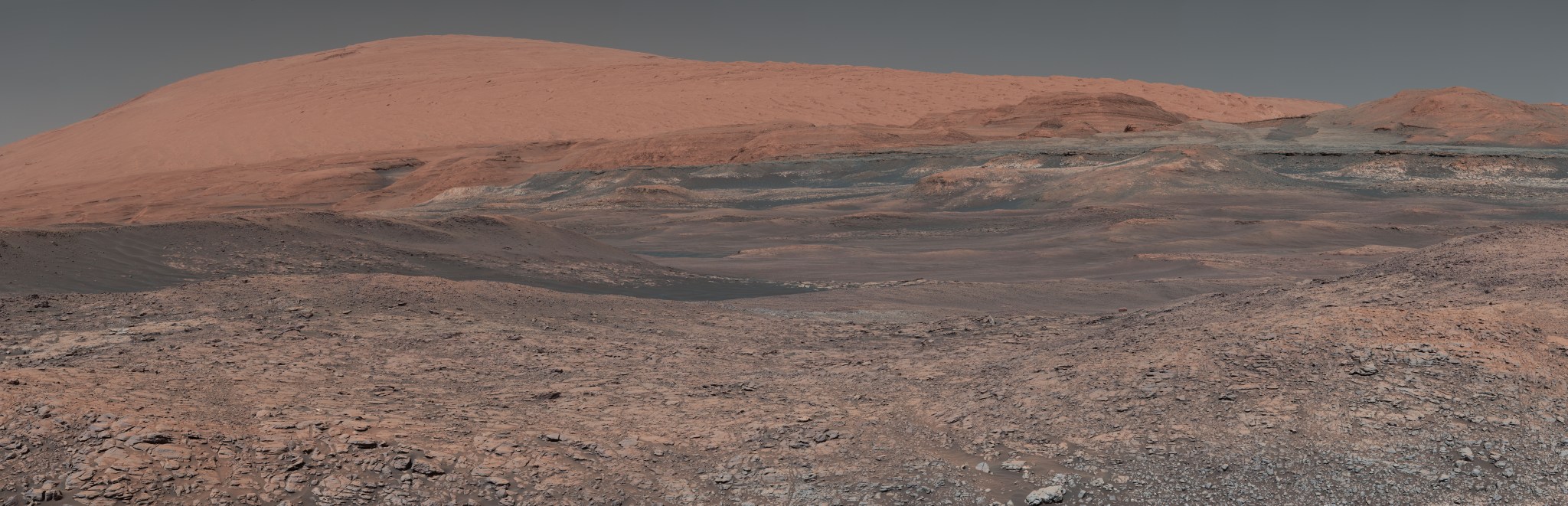

Known as the Red Planet because of the rust particles in its soil that give it a reddish hue, Mars has always fascinated the human mind. What would it be like to live on this not-so-distant world, many have wondered? One day, astronauts will find out. But we know already that living there would require some major adjustments. No longer would we be able to take long, deep breaths of nitrogen- and oxygen-rich air while a gentle spring breeze grazes the skin. Without a spacesuit providing essential life support, humans would have to inhale carbon dioxide, a toxic gas we typically exhale as a waste product. On top of that, the thin Martian atmosphere (100 times thinner than Earth’s) and lack of a global magnetic field would leave us vulnerable to harmful radiation that damages cells and DNA; the low gravity (38% of Earth’s) would weaken our bones. Besides the hardships our bodies would endure, it would simply be less fun to live on Mars. Summer trips to the beach? Forget them. On Mars, there’s plenty of sand, but not a single swimming hole, much less a lake or ocean, and the average temperature is around minus 81 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 63 degrees Celsius). Even the hardiest humans would find the Martian climate to be a drag. —Staci Tiedeken, planetary science outreach coordinator, NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

2. There’s solid ground to stand on

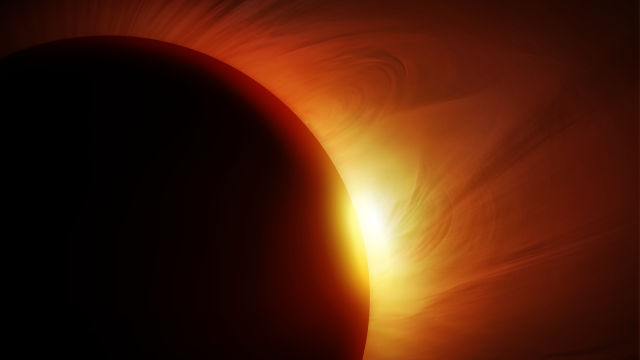

Earth has grassy fields, rugged mountains and icy glaciers. But to live on the Sun, we’d have to kiss all solid ground goodbye. The Sun is a giant ball of plasma, or super-heated gas. If you tried to stand on the Sun’s visible surface, called the photosphere, you’d fall right through, about 205,000 miles (330,000 kilometers) until you reached a layer of plasma so compressed, it’s as thick as water. But you wouldn’t float, because you’d be crushed by the pressure there: 4.5 million times stronger than the deepest point in the ocean. Get ready for a quick descent, too. The Sun’s gravity is 28 times stronger than Earth’s. Thus, a 170-pound (77-kilogram) adult on Earth would weigh an extra 4,590 pounds (2,245 kilograms) at the Sun. That would feel like wearing an SUV on your back! If a person managed to hover in the photosphere, though, it might get a little warm. The temperature there is around 10,000 degrees Fahrenheit (5,500 Celsius), about five to 10 times hotter than lava — yet, not nearly the hottest temperature on the Sun. Don’t worry, though, there would be a break of 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit (1,600 degrees Celsius) if you stumbled on a sunspot, which is a “cool” region formed by intense magnetic fields. These conditions would have even the most intrepid adventurers longing for the comforts of home. —Miles Hatfield, science writer, NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

Credits: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

Download this video in HD formats from NASA Goddard’s Scientific Visualization Studio

3. The seasons go round and round

Since the beginning of recorded history, people have tracked and celebrated nature’s transition from the desolate days of winter, to the brilliant radiance of spring, to the endless days of summer, and so on. Seasons come from a planet’s tilt on its axis (Earth’s is 23.5 degrees), which tips each hemisphere either toward or away from the heat of the Sun throughout the year. Venus, barely tilted on its axis, has no seasons, though there are hints that it may have once looked and behaved much like Earth, including having oceans covering its rocky surface. But these days, our neighboring planet has an atmosphere so thick (55 times denser than Earth’s) it helps keep Venus at a searing 900 degrees Fahrenheit (465 degrees Celsius) year round — that’s hotter than the hottest home oven. This oppressive atmosphere also blots out the sky, making it impossible to stargaze from the surface. But Venus isn’t all bad. Despite the low quality of life, there is one benefit of living there: The Venusian year (225 Earth days) is shorter than its day (243 Earth days). That means you can celebrate your birthday every day on Venus! —Lonnie Shekhtman, science writer, NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

Credits: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

Download this video in HD formats from NASA Goddard’s Scientific Visualization Studio

4. Its gravity doesn’t turn us into noodles

Capturing the imaginations of scientists and sci-fi writers alike, black holes are extremely compact objects that do not let any light escape. The surface of a black hole is an area called the “event horizon,” a boundary beyond which nothing can ever return. Even if we were fortunate enough to have a spaceship that could travel to a relatively nearby black hole, its gravity is so strong that approaching too close would stretch and compress the spacecraft and everyone inside it into a noodle shape — a fate scientists call “spaghettification.” Making matters even weirder, time ticks by more slowly around a black hole. To someone watching from far away as a spaceship fell into the event horizon, the vehicle would appear to slow down more the closer it got — and never quite get there. Fortunately, there are no known black holes in the vicinity of Earth or anywhere in the solar system, so we’re safe for now. And we’re lucky that Earth has just the right amount of gravity — enough so we don’t go flying away, but not so much that we can’t stand up and run around. If you still think traveling to a black hole would be a good idea, check out this black hole safety video. —Elizabeth Landau, writer, NASA Headquarters

5. We can enjoy a pleasant breeze

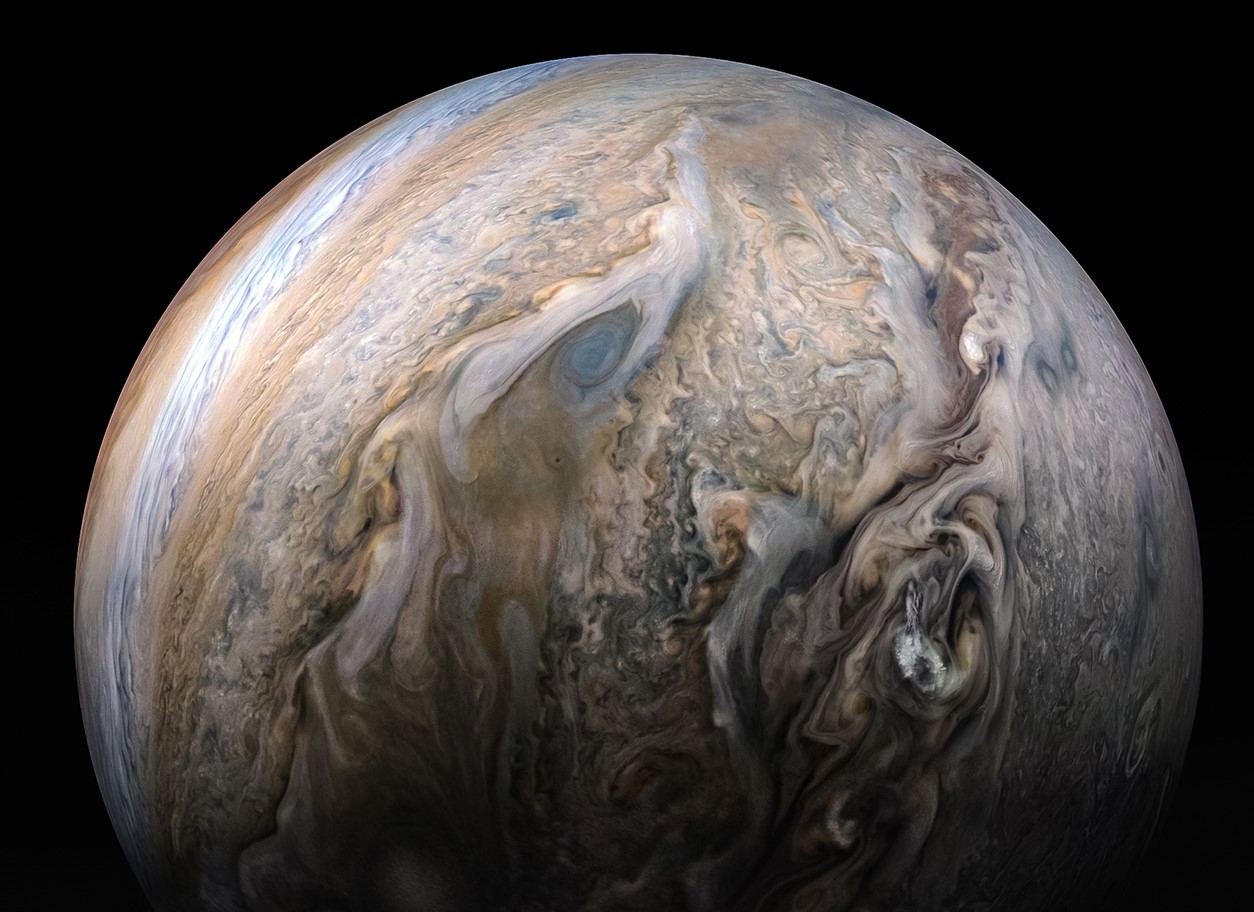

Jupiter’s breathtaking swirls of colorful cloud bands might make this planet an appealing vacation destination … for skydivers. They’d need to bring along their own oxygen, since Jupiter’s atmosphere is made mostly of hydrogen and helium (same as our Sun), with clouds of mostly ammonia. Descending through Jupiter’s clouds is for the most extreme thrill seekers. Given the planet’s strong gravity and super-fast rotation on its axis compared to Earth (10 hours vs. 24 hours), a skydiver would tumble 2.5 times faster than they would on Earth, while getting knocked around by winds raging between 270 and 425 miles per hour (430 to 680 kilometers per hour). Jupiter’s winds make Earth’s highest category hurricane feel like a breeze, and its lightning strikes are up to 1,000 times more powerful than ours. Even if a skydiver does make it through the hundreds of miles, or kilometers, of atmosphere, plus crushing air pressure and extreme heat, it’s not clear they’ll reach a solid surface. Scientist don’t know yet whether Jupiter, a giant planet that can fit 1,300 Earths inside of it, has a solid core. Having solid ground to stand is starting to sound like a luxury. —Staci Tiedeken, planetary science outreach coordinator, NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

6. It’s a sparkling globe of blue, white and green

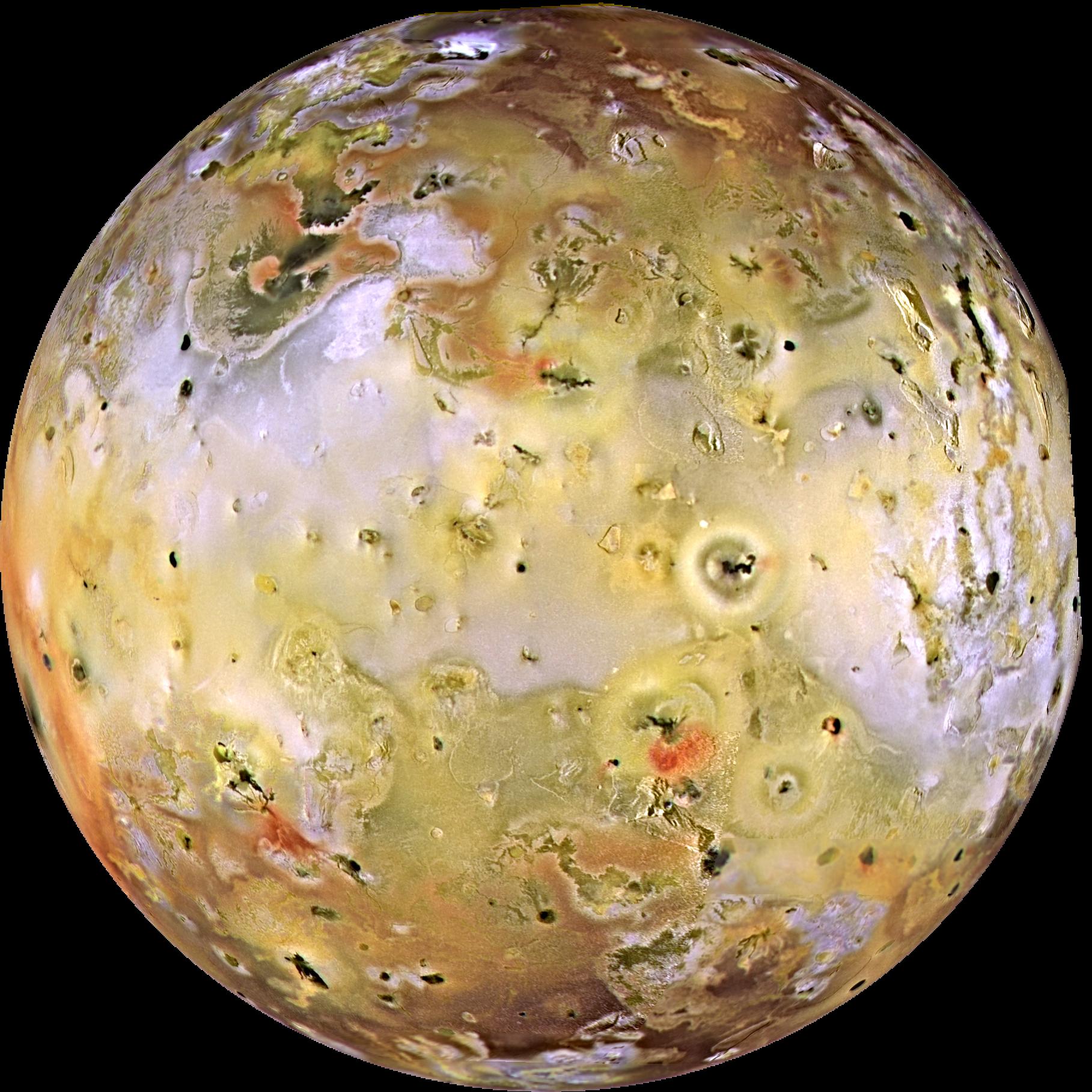

In places where ocean tides are highest on Earth, the difference between low and high tide is about 50 feet (15 meters). Compare that to Io. This moon of Jupiter is caught in a tug-of-war between the planet’s massive gravity and the pulling of two neighboring moons, Europa and Ganymede. These forces cause Io’s surface to regularly bulge up and down by as much as 330 feet (100 meters) — and we’re talking about rock, not water. All this motion has consequences: Io’s interior is very hot, making this moon the most volcanically active world in the solar system. Io, which from space looks like a moldy cheese pizza, has hundreds of volcanoes. Some erupt lava fountains dozens of miles (or kilometers) high. Between all the lava, a thin sulfur dioxide atmosphere and intense radiation from nearby Jupiter, Io doesn’t offer much of a beach vacation for humans. —Bill Dunford, writer and web producer, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory

7. It’s got clear skies, sunny days and water we can swim in

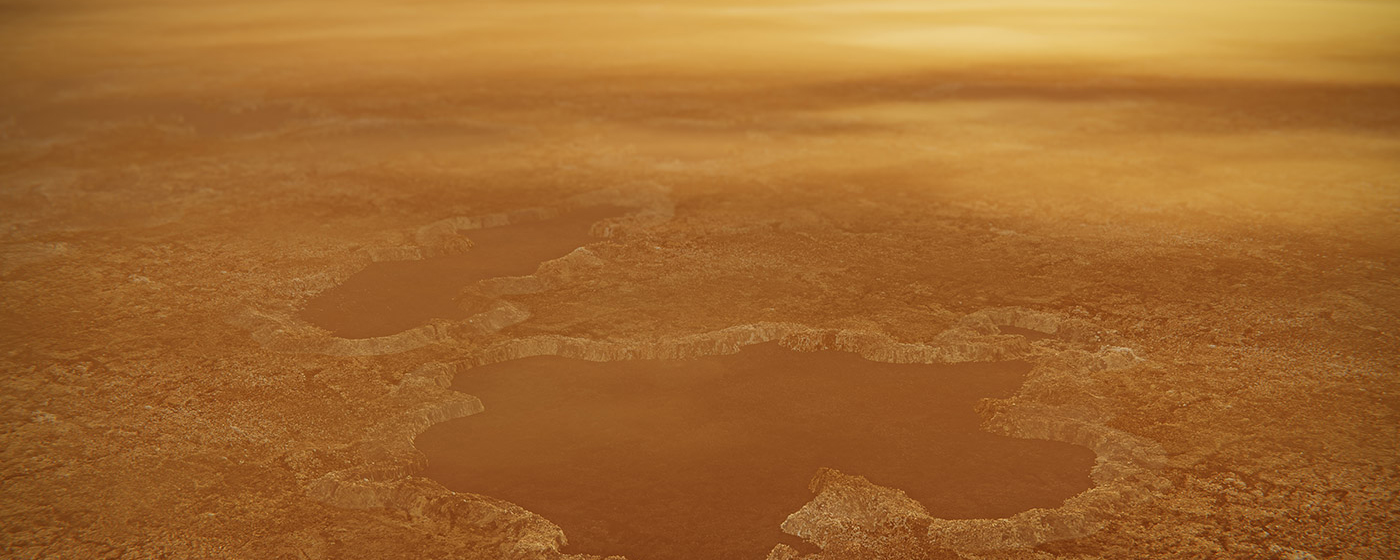

If there is one place in the universe we know of that could compete with Earth as a home for humans, Titan is it. This satellite of Saturn is the second largest moon in our solar system after Ganymede. Titan is in some ways the most similar world to ours that we have found. Its thick atmosphere would remind us of home, though the air pressure there is slightly higher than Earth’s. The atmosphere would defend humans against harmful radiation. Like Earth, Titan also has clouds, rain, lakes and rivers, and even a subsurface ocean of salty water. Even the moon’s terrain and landscape look eerily similar to some parts of Earth. While Titan sounds promising, it has major flaws. Chief among them is oxygen — there isn’t any in the atmosphere. And those lovely rivers and lakes? They’re made of liquid methane. So don’t pack your bathing suit just yet; our bodies are denser than the methane, so they’d sink like boulders. Another thing you’d miss on Titan is seeing the Sun above your head, dazzling against an azure sky. Not only is Titan much farther from the Sun than is Earth, its hazy atmosphere dims the sunlight, making daytime appear like twilight on Earth. —Lonnie Shekhtman, science writer, NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

8. Dry land exists! And the entire world isn’t smothered beneath miles of ice

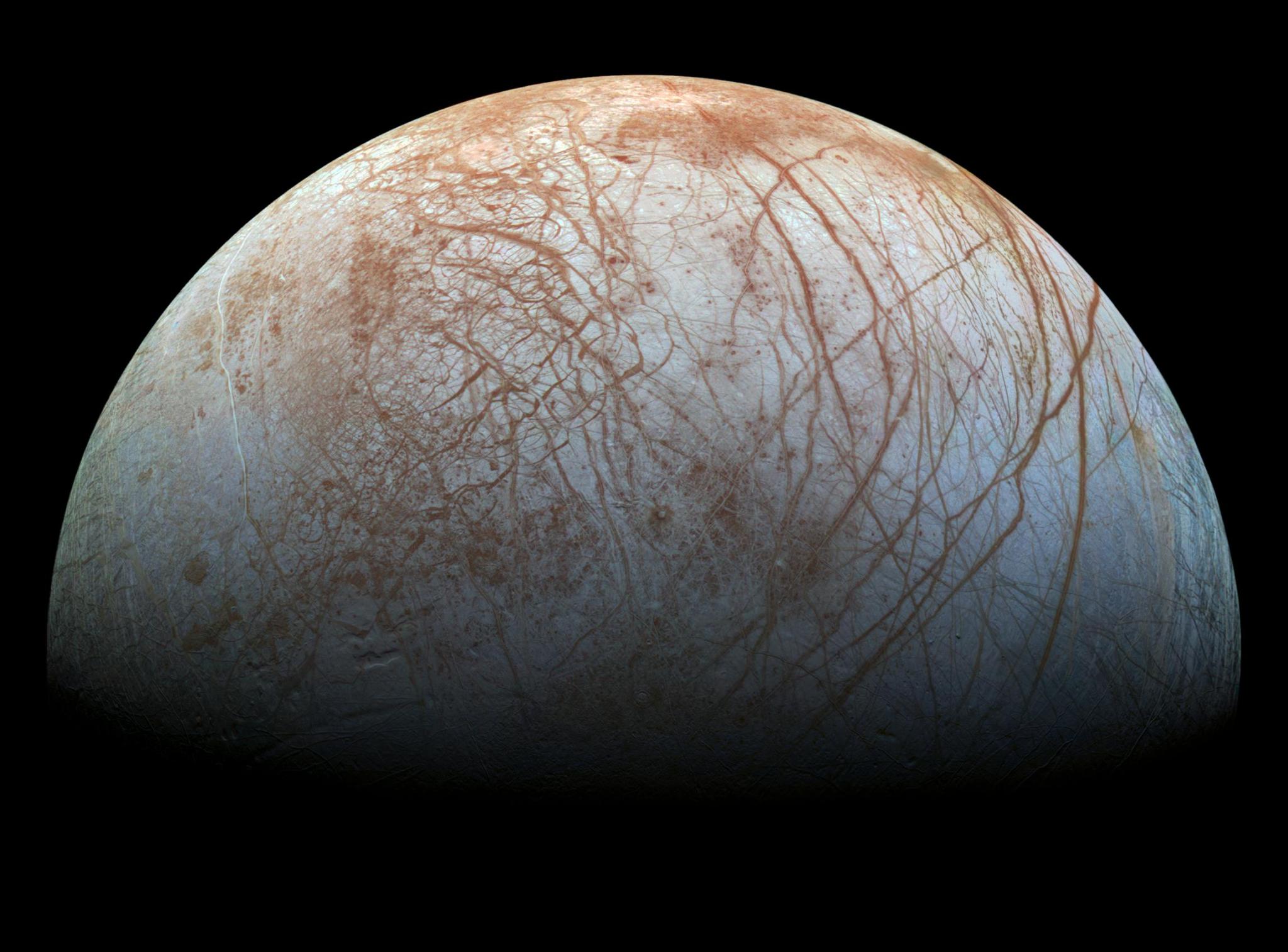

Jupiter’s moon Europa is one of the best places to search for life beyond Earth. It may harbor more liquid water than all of Earth’s oceans combined. Just picture yourself standing on a warm, sandy beach, admiring the sunlight glimmering on an ocean that reaches from horizon to horizon. And then prepare to be disappointed. Europa’s ocean is global. It has no beach. No shore. Only ocean, all the way around. Sunlight doesn’t glimmer on the water and there are no waves because Europa’s ocean is hidden beneath miles — perhaps tens of miles — of ice that encases the entire moon. Europa is also tidally locked, meaning if a person stood on its Jupiter-facing side (like our Moon, one hemisphere always faces its parent planet), the solar system’s largest planet would loom overhead and never set. A sublime setting for a romantic stroll? No. Europa has a practically nonexistent atmosphere and brutally cold temperatures ranging from about minus 210 to minus 370 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 134 to minus 223 degrees Celsius). A spacesuit might help with the temperature and pressure, but it can’t protect against those pesky atomic particles captured in Jupiter’s magnetic field, endlessly lashing Europa with such energy that they can blast apart molecules and ionize atoms. Europa’s ionizing radiation would damage or destroy cells in the human body, leading to radiation sickness. —Jay R. Thompson, writer, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory

9. Cream puff clouds that come and go

With more than 4,000 planets discovered so far outside our solar system, called “exoplanets,” we don’t know of any that offers the comforts of Earthly living — and many would be downright nightmares. Take Kepler-7b, for example, a gas giant with roughly the same density as foam board. That means it could actually float in a bathtub (fun fact: so could Saturn). Like other exoplanets called “hot Jupiters,” this one is really close to its star — a “year,” one orbit, takes just five Earth days. One side always faces the star, just like one side of the Moon always faces Earth. That means it’s always hot and light on one half of this planet; on the other, night never ends. If you’re bummed out by cloudy days on Earth, consider that one side of Kepler-7b always has thick, unmoving clouds, and those clouds may even be made of evaporated rock and iron. And at more than 2,400 degrees Fahrenheit (1,316 degrees Celsius), Kepler-7b would be a real roaster to visit, especially on the dayside. It’s amazing to learn about how different exoplanets can be from Earth, but we’re glad we don’t live on Kepler-7b. —Kristen Walbolt, digital and social media producer/strategist, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory

Last Updated: Apr 22, 2020

Editor: Svetlana Shekhtman