Hacking ICESat-2: How an Open Science Workshop

Helped Scientists Wrangle Big Data

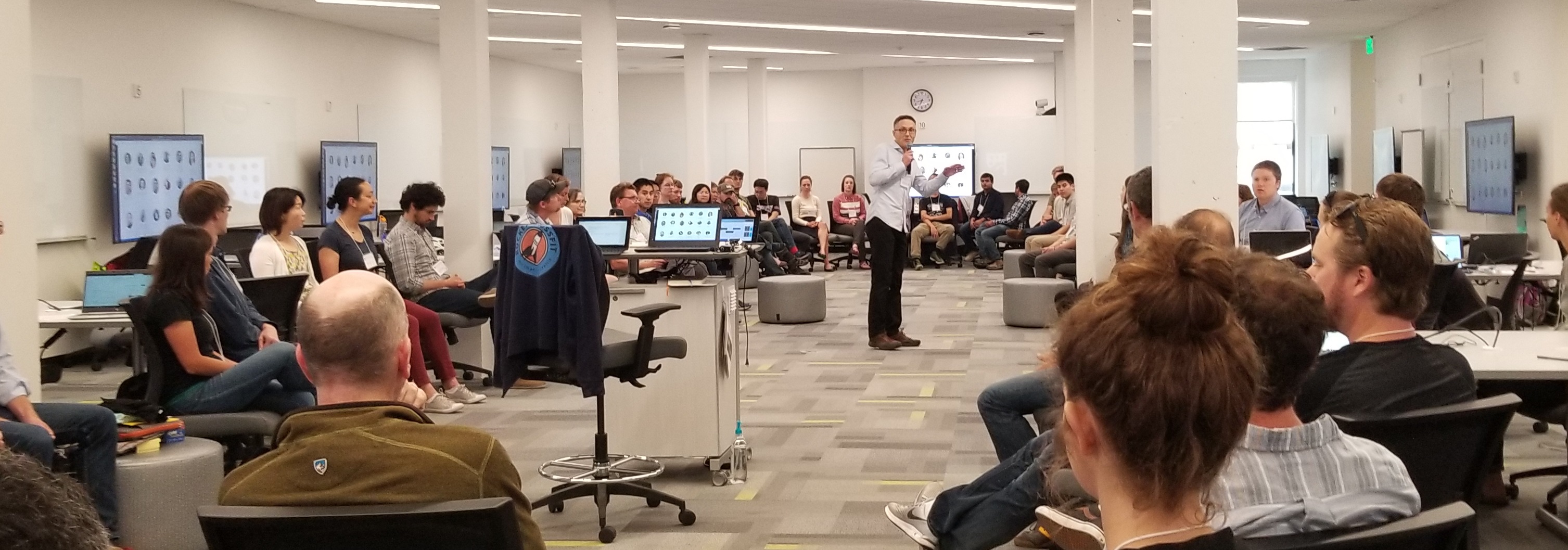

Above: ICESat-2 Hackweek collaborators gathered at the University of Washington (UW) in Seattle.

Photo credit: University of Washington

The Ice, Cloud, and Land Elevation Satellite-2 (ICESat-2) mission was launched in September 2018 to collect precise measurements of Earth’s cryosphere (sea ice, glaciers, and ice sheets) as well as the heights of forests, oceans, cities, and other geographic features.

The ICESat-2 spacecraft uses laser altimeters to provide scientists with huge and invaluable new elevation datasets with unprecedented (centimeter-level) precision. This rich, precise, and finely calibrated altimetry data will be collected continuously over a long period (optimally, for at least 3 years) along tracks that repeat often (every 91 days). ICESat-2 provides both an exceptional opportunity for study and also a rigorous challenge for researchers, in terms of processing, managing, distributing, and analyzing its massive and complex datasets.

To address that challenge, 20 scientists from organizations including NASA Goddard in Maryland, the University of Washington (UW) in Seattle, and the National Snow and Ice Data Center in Boulder (the distribution center for ICESat-2 science data) worked for a year to plan and facilitate a one-week, collaborative, intensely productive workshop: the ICESat-2 Hackweek.

Leading this collaborative effort was Anthony Arendt, a cryospheric scientist at UW’s Applied Physics Laboratory (APL), a Senior Data Science Fellow at the eScience Institute, and an experienced leader of hackweeks focused on various topics that grew out of work done at eScience over the past several years. Arendt led a team of 20 facilitators including ICESat-2 Project Scientist Tom Neumann of NASA Goddard’s Cryospheric Sciences Laboratory to collaboratively plan and support the event.

Above left: ICESat-2 Hackweek participants collaborating in one of UW’s active learning classrooms. Above right: Participants sharing a catered lunch, networking, and enjoying a great view of Puget Sound.

Photos courtesy University of Washington.

This open-science hackweek took place at UW’s South Campus Center in Seattle June 17–21, 2019. Hackweek facilitators and 60 workshop participants worked closely together in agile groups over the course of the week. The teams developed and refined tools and processes together to parse ICESat-2 datasets in different ways, forming new ideas about data analysis tools and methods, potential research projects, and project team possibilities during their time together. In at least a few cases, the productivity of the workshop has resulted in more scientists being interested in, and better able to take advantage of, ADAPT science cloud resources from the NASA Center for Climate Simulation (NCCS).

Below, in their own words, are blogs from the planners, facilitators, and participants of ICESat-2 Hackweek. It’s an intriguing, inside look at how and why it evolved, what happened during the event, and some of the results.

How would you describe yourself?

I’m a glaciologist at the University of Washington (UW) in Seattle.

How and why did the ICESat-2 Hackweek come about?

About a year ago, former Cryospheric Sciences Program Manager Tom Wagner was in Seattle for a workshop I led. We hosted it in an "active learning" classroom on the UW campus that is often used for software trainings. Wagner liked the interactive format of the workshop and suggested we host something similar to facilitate the development of tools for accessing data from ICESat-2. The idea was to build a community that could work together in sharing software so as to minimize duplication of effort and maximize the opportunity for doing high-impact science with the data. I worked with Wagner and suggested the hackweek model would be a good fit for achieving these goals.

What is the history of hackweeks, generally, at UW?

The hackweek concept was designed by my colleagues at the UW eScience Institute. It started within the astronomy community. It then extended to the neuroscience community, and I helped apply the model to the geosciences (see geohackweek.github.io). Hackweeks strive to create a welcoming learning environment to foster community building, opportunities for software development and training in open source, reproducible data science methods. I teamed up with several colleagues to create a white paper with more details on the hackweek model.

Who organized the event?

Anthony Arendt, Axel Schweiger, Ian Joughin, and Ben Smith (all with APL's Polar Science Center) polled the ICESat-2 community, looking for volunteers to help lead tutorials and share knowledge on existing software within the community. A core team of nearly 20 people then began meeting regularly via video conference to design the event. The team included graduate students, technicians, research scientists and faculty. The full schedule, as designed, including links to tutorial content, is here: https://icesat-2hackweek.github.io/schedule.html.

What happened during the event?

About 60 participants attended, with about 20 facilitators supporting the participants. Everyone was given access to a shared cloud computing system on Amazon Web Services so that we could have everyone using a common computational platform. Each day, the mornings involved interactive tutorials on software tools and algorithms used to access and filter the ICESat-2 data.

Day 1 involved introductions to the ICESat-2 sensor from science team members. It also involved training in core data science collaboration tools. Afternoons involved open project time. On day 1, we facilitated a session in which individuals pitched project ideas, and the remaining participants moved around the room to talk to different groups and decide on which project they would like to join. More information on projects is here: https://icesat-2hackweek.github.io/wiki/project_guidelines.html.

ICESat-2 Hackweek leader Anthony Arendt welcomes the collaborators.

Photo courtesy Alek Petty.

All teams used a collaboration software called GitHub to share their work. The full catalog of projects developed this year is here: https://github.com/ICESAT-2HackWeek/projects_2019

On the final day, the participants presented their work to each other. Most of the tutorials and talks have been recorded and will be posted to YouTube shortly. Data scientist Fernando Perez offered some of the core introductory tutorials. Fernando is not associated with ICESat-2 or cryospheric research—I know him through our connections in the data science community. Fernando is a core developer of many important data science toolkits including the Jupyter project, and his contribution to the event was invaluable.

What are the outcomes of the event?

Everyone agreed the tutorials will be valuable resources to reference in the future. Therefore, efforts are underway to formally share the content using Zenodo, which would give them a version number and DOI.

There was considerable interest in developing a core set of Python libraries that would contain the basic data science tasks associated with using ICESat-2 data. This library could include steps for downloading, subsetting, filtering and doing simple visualizations with the data. Everything would be built out of the tutorials developed for the event. The hope is that other researchers could then access this library and not have to rewrite these basic scripts each time they want to work with ICESat-2 products. I and others are hoping to lead this effort moving forward, in partnership with NSIDC and the broader ICESat-2 community.

Any final thoughts?

A reflection I can offer is that I was extremely impressed by what this community accomplished in 5 days. I did my postdoc at NASA Goddard from 2006—2008, right after ICESat-1 was launched. I recall just how challenging it was, at the time, to access the data and to know how best to filter and process the data for my science applications. What I saw during the ICESat-2 hackweek was a desire to work together and to pool our collective resources so that everyone could begin doing their science. I hope we can keep this momentum going and potentially host a similar event again in the future.

Anthony’s Bio: http://psc.apl.uw.edu/people/investigators/anthony-arendt/

ICESat-2 Hackweek Pages

Schedule: https://icesat-2hackweek.github.io/schedule.html

Instructors and Event Coordinators: https://icesat-2hackweek.github.io/our-team.html

Pre-Event Tutorial: https://icesat-2hackweek.github.io/preliminary/

ICESat-2 Project Scientist Tom Neumann and his team working on the

2-week, South Pole Traverse fieldwork for the ICESat-2 Mission.

Photo courtesy Tom Neumann

What inspired you to become a cryospheric scientist?

How did I get here ….what initially piqued my interest in the cryosphere was a course in college (Univ. of Chicago) on the Ice Age Earth, taught by Doug MacAyeal. It really surprised me that although there was ample evidence for the growth and decay of the great ice sheets, we/scientists really didn’t have a good explanation for why. The last ice age really just ended 14,000 years ago, which is a blink of an eye in geologic time. How was it possible that we fundamentally didn’t have a good handle on how the world could change so dramatically? That sent me off the path of learning how glaciers and ice sheets move and change through time, and how to preserve a record of the past environment. That was in … 1994. 25 years later and I’m still at it…

What was your role at the ICESat-2 Hackweek?

Beyond representing the ICESat-2 mission as the Project Scientist, I also led the part of the team that developed the geolocated photon cloud data product (which we call ATL03). That data product provides a latitude, longitude and height for every photon that ATLAS records and processes. So at the Hackweek, I was also there to tell people about ATL03 and help them get started using it.

Is NCCS/ADAPT involved in this particular hackweek in any way? And, if so, how so? Is it the processing and distribution of the raw ICESat-2 data?

Our DAAC is the National Snow and Ice Data Center. However, there are a handful of other data distribution and access groups that have value-added services, in addition to simply serving the data. ADAPT is among those: by bringing the ICESat-2 data into the cloud environment, scientists have the ability to bring a large amount of computational power to bear. ADAPT is specifically called out as a resource in the open solicitation for proposals to do science with ICESat-2. ADAPT will be a key component of scientist use of ICESat-2 data. [Note from the Editor: See Ellen Salmon’s interview below for more information about ADAPT.]

ICESat-2 is primarily designed for collecting cryospheric elevation measurements (glacier and sea ice height), but the instrument can be used to measure the elevation of other Earth features (such as oceans, deserts, and forest vegetation) and used by researchers in several scientific disciplines. Is multidisciplinary research important to science?

Multidisciplinary research is a key part of where cutting edge science is going. We really can learn more by combining many different measurement strategies than we can learn from any one individual measurement. This increases the value of the data by opening up new science through the combination of measurements.

For example, ICESat-2 has been collecting elevation data over the world’s forests, in addition to the poles. By using the tree coverage spatially from the long-term series of imagery from Landsat and other optical sensors, we can better guide the ICESat-2 algorithms to estimate tree height.

Tom's NASA Page

Main NASA ICESat-2 Page

ICESat-2 Technical Specs

ICESat-2 Launch Video (and the final Delta II rocket launch)

Prior Interview of Tom and the ICESat-2 Team (NASA EDGE: Best of ICESat-2 Rollback Show – YouTube)

I’m a glaciologist and Assistant Professor in the Department of Geosciences at Boise State University, and I was a full-week participant in the ICESat-2 Hackweek.

I heard about the ICESat-2 Hackweek early in the winter of 2018 and was immediately interested in attending the workshop. I knew that ICESat-2 data are going to be fundamental to advancing the present understanding of glacier change, since analysis of laser altimeter data (from ICESat, Operation IceBridge, etc.) has already been immensely beneficial to the cryosphere community. I have used Operation IceBridge data in the past, but understood that there was going to be a steep learning curve with the ICESat-2 data, and I was interested in getting semi-formal training and hands-on experience working with the data at the workshop.

Fortunately, I just started a tenure-track faculty position at Boise State University and was able to use some of my start-up funds for workshop expenses. I had several students attend the workshop as well, and they all received early-career funding from the workshop that was essential for them to attend. It's normally difficult to spend a full week at a workshop because you feel like you are not maximizing use of your time when you are already so time-limited, but I thought the ICESat-2 workshop was a terrific use of my time: the tutorials that walked us through how to download, visualize, and process the data will be incredibly helpful as I start to work ICESat-2 data into my projects.

The group work throughout the workshop was incredibly valuable as well, especially since I am relatively new to Python (I do most data analysis in MATLAB). Python is encouraged for ICESat-2 data analysis in order to promote an open-science community, and the workshop provided a platform to gain Python proficiency while working with colleagues from a variety of universities and with a range of experience levels. The group work also allowed me to look at the data in detail, validating the feasibility of a project idea that I plan on submitting to the ICESat-2 solicitation this fall! I've been thinking about writing in use of ADAPT [a resource of the NASA Center for Climate Simulation, NCCS] into the proposal to optimize efficiency working with such a terrific but large dataset.

Ellyn’s University Page

Ellyn’s Personal Page

Above, right: Alek Petty brought the youngest participant to the Hackweek

event, daughter Raina Stone Petty. Photo courtesy Alek Petty.

I'm an assistant research scientist in the Sciences and Exploration Directorate at NASA Goddard and the University of Maryland. I study polar sea ice variability and its connections with the global climate system. I led some of the sea ice tutorials at the ICESat-2 Hackweek and provided some advice to the various sea ice groups formed during the event.

The hackweek was very inspiring! It's surprisingly uncommon to have scientists in our community actively working together to explore data and solve problems in real-time, especially mid/late career scientists. It provided a more dynamic and engaged environment compared to the more traditional format of workshop/conferences (talks, minimal audience participation), and there was some great networking going on too.

I think a big part of the success of the event was the fact that the hackweek was based upon understanding this new big, shiny satellite dataset that people across cryospheric sciences seem to realize could be a real game-changer. The participants seemed to accept the idea that it's worth spending some time and energy grappling with the data in this setting, as they were surrounded by like-minded scientists and people more directly involved with the project who could help troubleshoot the obvious challenges of reading in and understanding big datasets like this.

I was really pleased to also see the more senior researchers being active in their groups and getting embedded with teams trying to understand how to work with the data, and not just leaving that to the younger scientists. Again, I think there were huge indirect benefits of this: exposure of younger scientists to more experienced researchers in the field, networking, etc.

The preparation was challenging! We were putting together tutorials to describe data that had only recently been made publicly available. We were trying to guess what might be most needed for the scientists, and some issues cropped up during the week with some documentation being unclear, although no obvious errors were found in the data to my knowledge. It was a real stress test of the data and our own understanding, which was obviously tough but hugely beneficial to us in the project.

I wouldn't be surprised if multiple variants of these projects were submitted to the upcoming ICESat-2 funding call. It seemed a great way for people to form new partnerships around common interests and carry out the preliminary analysis needed to see if these ideas could form the basis of a full scientific proposal.

I'm very much hoping to use ADAPT going forward! It offers the most efficient way of accessing ICESat-2 data directly in the cloud and running analysis in this same high-performance computing environment. Platforms like ADAPT are the future of scientific programming environments as our datasets get ever bigger and our analysis toolkits become more sophisticated.

Alek's Bio

I'm a Ph.D. student at the Centre for Polar Observation and Modelling (CPOM) in London, researching the properties of snow on Arctic sea ice. A few weeks ago, I attended a 5-day hackweek organized by the University of Washington Polar Science Center and the eScience institute, taught by members of the NASA ICESat-2 science team. The hackweek was made up of tutorials on data access and manipulation as well as collaborative projects on polar science.

During the workshop, we were quickly encouraged to pitch our ideas for projects, with attendees proposing ocean wave detection, mapping of ice sheet grounding lines and calculation of floe size distribution. I proposed a project to investigate the automatic blowing snow detection algorithm and was very pleased to have five people join my project! I wanted to compare the data to weather data from climate models, but we quickly branched out to mapping the distribution of blowing snow too.

We made a convincing climatology and our comparisons to reanalysis were encouraging, but we limited our scope to land-ice for practical reasons. We're now planning to extend our work to the ICEsat-2 sea ice product, where a climatology of blowing snow has never been made (to our knowledge).

A significant part of the week focused on software tools like cloud computing in Jupyter Lab and Git, a collaboration and version control tool. It was great to be pushed to use these tools, as I wouldn't have done so otherwise. Git in particular offers our blowing snow team a chance to continue developing our product even now that the hackweek is over.

As well as the chance for ongoing collaboration on blowing snow, ICEsat-2 has a lot to bring to my Ph.D. project. I'm currently working on radar altimetry of the sea ice surface and encumbent assumptions about the spatial patterns of snow cover. ICEsat-2 offers the chance to validate radar altimetry, and also to shed light on model-generated snow distributions. During the hackweek I also had a couple of other ideas for novel uses of the data, which I'm going to keep under my hat for now! Perhaps just as valuably, I made some great connections with other Ph.D. students with expertise in connected areas.

It clearly took a lot of time and effort to make this happen; thanks go in particular to the University of Washington eScience institute and Polar Science Center, and Anthony Arendt who brought it all together. I'm looking forward to all the icy science to follow!

[Editor’s note: This was just a preview of Robbie's blog]

I’m the Data Services Lead at the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC). I’ve been a member of NSIDC’s Science Communications Group for over 4 years, with a background in stable isotope biogeochemistry. I specialize in ICESat-2 user support, tool and service development, and data education resources for NSIDC’s growing user community.

I supported the ICESat-2 Hackweek before and during the entire hackweek. I was not involved the hackweek genesis per se, but I worked with the instructor group on the creation of the tutorial content for several months prior to the event.

Above: Amy Steiker, in the center of the room, works on a Jupyter

Notebook, providing data access and subsetting for the teams

I worked on a Jupyter notebook on data access and subsetting that leveraged NSIDC’s Application Programming Interface (API) to subset and access data over a glacier in Antarctica, and this data was used in many of the hackweek projects throughout the week.

Because ICESat-2 data were just released at the end of May, most hackweek participants were new to the mission, and there was a clear need to programmatically access and subset the data in order to reduce preprocessing steps. So it was valuable for me to be there representing NSIDC in order to provide guidance on data access, services, and other resources available through our website, although all instructors contributed a tremendous amount of material and guidance for the participants. It would not have been a successful event without the combined effort across the instructor team as well as the administrative team and the participants themselves!

[Editor’s notes from the web: The National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) Distributed Active Archive Center (DAAC) provides data and information for snow and ice processes, particularly interactions among snow, ice, atmosphere, and ocean, in support of research in global change detection and model validation. NSIDC serves as one of twelve Distributed Active Archive Centers (DAACs) funded by NASA to archive and distribute data from NASA's past and current satellites and field measurement programs.]

Amy’s Linkedin Page

NSIDC Home Page

NSIDC ICESat-2 Page

I’m an Assistant Professor at the University at Buffalo’s Department of Geology. I made it a priority to attend the ICESat-2 Hackweek. I applied to attend it nearly as soon as the application opened and prioritized my summer work schedule around the week-long event.

ICESat-2 Hackweek collaborators share a catered lunch on

the Observation Deck outside of the classroom.

I saw the value in instruction, training, and guidance in accessing and working with the new ICESat-2 dataset. It’s “bigger” data than I’ve worked with before, which requires new approaches than I’ve previously used. At the workshop, I learned all these things as well as some bigger-picture ideas of working in an open-source environment and using and contributing to open-source tools.

The workshop was intensive; it required us to assimilate and apply a large amount of new techniques quickly/drink from the firehose. Thanks to the open-source framework, all of the training materials and everything developed during the hackweek by the participants are available online, perpetually, which allows me to review and build on the work we did during the week. The hackweek was exceptionally well organized and facilitated.

Kristin Poinar’s University Page

Kristin Personal Page

I’m a field glaciologist and a post-doc at the University of Oregon. I use remote sensing and field measurements to study glacier hydrology and ice-ocean interactions. I often use optical imagery in my research, but saw the ICESat-2 hackweek advertised (on CRYOLIST) and decided that this would be a great opportunity to dive into a new type of sensor, so I used my vacation time to attend. I was able to stay nearly the entire week, but had to leave a day early to head to Greenland for fieldwork. The hackweek itself was unlike any individual academic experience I have had, while at the same time encapsulating all of the best qualities of academia: scientifically intriguing, motivating, and productive.

Prior to the hackweek, all participants received a schedule, but I was new to the idea of hackweeks so had absolutely no expectations going in. If anything, I was actually a bit apprehensive since I had only just started coding in Python (the programming language used during hackweek) as opposed to MATLAB. Each day, we had a combination of instructional sessions, working time, and discussion within and between groups. The groups were self-arranged based on research focus with the addition of a rotating ICESat “expert” in each group. Three of our five group members spoke prior to hackweek, so we went in having a research focus, which may have been different than other groups.

The work time and instructional sessions were intense, but luckily the rotation between activities and being able to troubleshoot errors with the ICESat-2 experts greatly decreased mental burnout and helped productivity and idea development. Our group ended up having very similar levels of ICESat-2 knowledge (not much) but strengths in different applications, so we worked together to get to a solid starting point using ICESat-2 data.

Since leaving UW, we have continued to work on our project (after a little mental break) with the intention of submitting a proposal to the ROSES call. Overall, hackweek exceeded all of my (non)expectations. I not only was able to dive into a new type of data and devote an entire week to learning a new skill, but also met a lot other researchers, especially those working on sea ice research, with overlapping interests and questions.

Kristin Schild’s University Page

What is your role at the NASA Center for Climate Simulation (NCCS)?

I’m a senior member of technical staff in the High Performance Computing group at the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. I focus on Technical User Services and operational support of Data Services for the NCCS.

How are you involved with the NCCS ADAPT Science Cloud?

I serve as a focal point for communicating, analyzing, and coordinating the NCCS's operational responses to science users' specialized requirements, such as those for approximately six Field Campaigns that NCCS supports each year.

Is there a connection between ADAPT and the ICESat-2 Hackweek event at UW?

Yes! I’d like the research community to know that copies of ICESat-2 data products and many other relevant data sets will be mounted on the NCCS ADAPT virtualization environment. ADAPT is a resource in the ROSES call for ICESat-2 research, providing compute resources around large data repositories, so researchers won’t have to move the data. ICESat-2 data are also available on the NCCS Discover HPC Linux cluster. In addition, NCCS is working on making Jupyterhub available for ADAPT Virtual Machines (VMs). NCCS also provides an ESRI ArcGIS infrastructure for scientific research.

More About ICESat-2 Hackweek (the event)

Event Page

ICESat-2 Hackweek Schedule

More ICESat-2 Hackweek Articles/Blogs/Photos

Blog by Scott Henderson:

More About ICESat-2 (the instrument)

Main ICESat-2 Page

ICESat-2 South Pole Ground Traverse- Story by NASA Science Writer Kate Ramsayer

ICESat-2 Images from the Scientific Visualization Studio (SVS) at NASA Goddard

https://svs.gsfc.nasa.gov/13044

http://svs.gsfc.nasa.gov/12905

ICESat-2 Data - Story by NASA Science Writer Josh Blumenfeld

ICESat-2 Antarctic Ground Traverse YouTube Video

Producer: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center/Ryan Fitzgibbons

Sean Keefe, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center